By Isabel Song Beer, Brooklyn Paper

July is on average New York City’s hottest month of the year, and with climate change steadily heating up the planet, summer months will undoubtedly increase in temperature: the first week of July this year was the hottest week ever recorded, with global temperatures breaking previously-set record highs.

While nearly 90% of the city has access to air conditioning, air conditioning in public housing is rare – with 76% of lower income New Yorkers going each summer without access to A/C.

Some city-led programs, such as the HEAP Cooling Assistance program, eligible households get access to free air conditioning units or fans to provide at-risk New Yorkers with some relief on a limited basis, but these resources are not often widely available.

Resources to help New Yorkers stay cool are limited

However, for the city’s more comprehensive cooling services to be made accessible, a heat advisory must be issued by the National Weather Service.

Heat advisories occur when the heat index forecasts temperatures of 95 degrees Fahrenheit or higher for two or more days, or when temperatures exceed 100 degrees for any extended period. There has yet to be an active heat advisory this summer.

These cooling centers — often based in community centers such as libraries, senior facilities and NYCHA facilities — are free, public air conditioned spaces designated for individuals to seek relief from the heat.

“Right now we follow the guidelines set by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene from their findings of their heat vulnerability index study,” Anna McCullough, the disability access and functional needs human services specialist at OEM, told the Brooklyn Paper. “Those studies have shown that the heat index of 95 degrees or higher is when NYC residents see more health impacts from heat.”

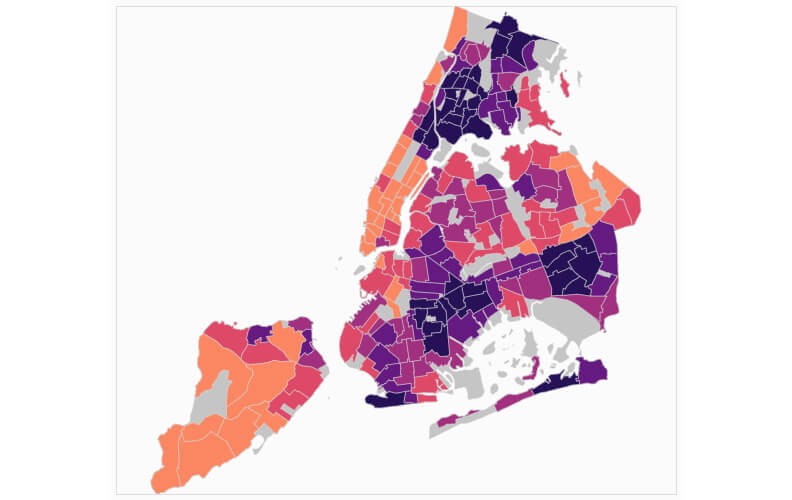

The New York heat vulnerability index is a map that was developed to help public health officials identify how likely individuals in certain communities are to be injured or killed due to heat.

Four factors go into determining the heat vulnerability of the city’s neighborhoods, including language vulnerability, elderly isolation and elderly vulnerability, socioeconomic and environmental and urban vulnerability.

The heat vulnerability index uses several factors to determine how vulnerable New York City neighborhoods are to serious heat illness. Neighborhoods in orange are the least vulnerable, while dark purple neighborhoods are the most at-risk.

Image courtesy of NYC Health and Environment Data Portal

Public health officials can use the heat vulnerability index to establish which areas experience the most heat-related illness or death and use the map to plan and make decisions on where to focus efforts to help keep residents cool and safe by establishing cooling centers, transportation, at home visits for elderly residents and more.

Cooling centers have been the source of some criticism in recent years, with elected officials calling for more frequent access to the services and for more facilities to be established in communities disproportionately represented in the city’s heat vulnerability index.

Vulnerable neighborhoods face the most risk

Last year, City Comptroller Brad Lander’s office released a report which indicated that ten Brooklyn neighborhoods were at particularly high risk for heat-related illness, with East Flatbush topping off the list.

Despite the higher risk for heat illness and vulnerability, only two cooling centers operate in East Flatbush; one at the Remsen Neighborhood Senior Center and the other at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Rugby Library.

“What we found about cooling center distribution is that East Flatbush was the most underserved by cooling centers per capita of the 162,000 East Flatbush residents,” said Louise Young, Chief Climate Officer at the Comptroller’s office. “There were only two cooling centers available for the whole neighborhood. And East Flatbush is a community that is considered high heat vulnerable according to the heat vulnerability index, so there’s a lot of reasons to be concerned for the limited number of centers there for those residents.”

Along with this report, the Comptroller’s office also issued a number of recommendations to ensure more New Yorkers are able to stay safe and cool during the summer months including increasing the number of cooling centers, especially in underserved neighborhoods like East Flatbush, increasing weekend hours at cooling centers, and more.

Many cooling centers close for the day in the early evenings, or are not open seven days a week — leaving New Yorkers who rely on them without options no matter how high the temperature is.

On average, approximately 350 New Yorkers die each summer from heat-related illnesses or heat stress, and Black New Yorkers are twice as likely to die from heat-related illnesses than their white counterparts.

With climate change set to increase that number, many advocates are scrambling to find solutions to make services like cooling centers more accessible.

City can’t promise more cooling centers in Brooklyn’s hottest neighborhoods

The OEM is currently limited to only opening centers when heat advisories are in effect, and accessibility to services is further limited as the OEM is not responsible for the operations of cooling centers, which are individually run by community partners the office collaborates with.

Additionally, because each cooling center operates in compliance with their own availability and capacity requirements, the OEM is not able to provide exact figures with regard to how many centers may actually be open and available on days where a heat advisory is in place. The office could not confirm whether or not more cooling centers would open in East Flatbush or other vulnerable neighborhoods after last year’s report from the Comptroller.

This may hinder how residents are able to get to cooling centers since the OEM’s cooling center interactive map is also only available during heat advisories.

“The cooling center finder is only activated during a [heat advisory] activation because it is updated in real time,” McCullough said. “And we don’t have a published list of our cooling centers every year because they do vary so widely throughout the summer and the activation days themselves.”

Red Hook Pool, 2017. Photo by Susan De Vries

This need-based real time activation is in place, according to the OEM, to ensure that residents don’t waste time and potentially risk their health traveling to cooling centers that could be closed.

“We really really want to keep people away from not checking and walking to a facility that may be closed that day, that can be really dangerous” McCullough explained. “So we really encourage everybody to call 311 and check the cooling center finder, so that’s the reason why it’s only activated during a heat activation.”

However, not everyone agrees with this methodology, with one of the Comptroller’s recommendations including making cooling center information permanently available.

“When there’s no heat wave or if you look at your weather app and you see, oh in like three days it looks like there’s gonna be a heat wave, where should I go?” said Young.

To further improve accessibility to cooling centers and to combat heat-related deaths and illness, Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso’s office is working to advocate for increased services for residents within the borough, especially those in high heat-risk neighborhoods like East Flatbush.

“What I’m hoping is that this is an issue of infrastructure versus resources,” Reynoso said. “Does East Flatbush have senior centers or schools or community centers that could be activated for a cooling center? And if they’re not, then we can work towards advocating for that to happen. But if it’s an infrastructure issue then we have to be creative and think outside the box. We are hoping that in the near future you will and can see advocacy related to the equity conversations and cooling centers.”

To be alerted when a heat advisory is in place or to be notified in the case of other city emergencies, sign up for NotifyNYC.

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.